You've spent years in your field. You know the terminology, the frameworks, the nuance behind every decision. That expertise is hard-won — and it might be getting in your way.

There's a phenomenon called the curse of knowledge. Once you know something deeply, it becomes almost impossible to remember what it was like not to know it. The language that feels precise to you sounds like static to someone hearing it for the first time.

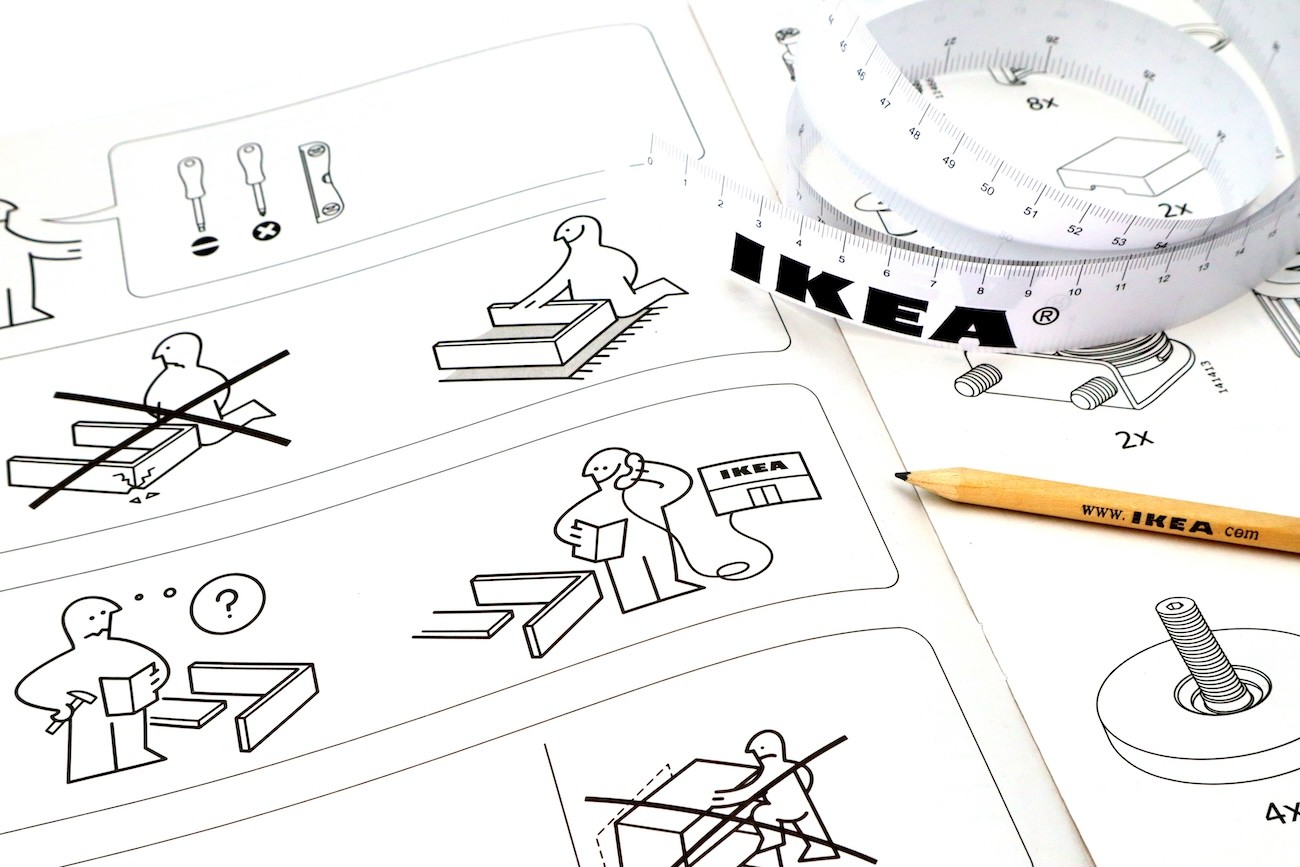

This shows up everywhere. The nonprofit that describes its work in grant-speak. The ministry that leans on theological shorthand. The company that stuffs its website with industry jargon. None of it is wrong, exactly. It's just not written for the people it's trying to reach.

The instinct is understandable. Specialized language signals credibility. It shows you belong. But belonging to your industry isn't the goal — connecting with your audience is. And connection requires meeting people where they are, not where you are.

This isn't about dumbing things down. It's about translation. When Steve Jobs introduced the iPod in 2001, he didn't talk about gigabytes or storage capacity. He said it was "a thousand songs in your pocket." The engineers knew the specs. The audience needed to know why it mattered.

The best communicators do this instinctively. They swap jargon for plain language. They trade abstraction for concrete examples. They remember that the people they're talking to aren't in the weeds — and most of them don't need to be.

A simple test: read your copy out loud to someone outside your field. Watch their face. Do they nod along, or do their eyes glaze over? That reaction tells you more than any internal review ever could.

Your audience doesn't need to understand everything you know. They need to understand why it matters to them. And that only happens when you stop writing like an insider and start writing like someone who remembers what it’s like to be in their shoes.